Some of you may know I’m currently developing a video game. So I’m going to talk a little bit about where that process is and the things I have to think about while I am doing it.

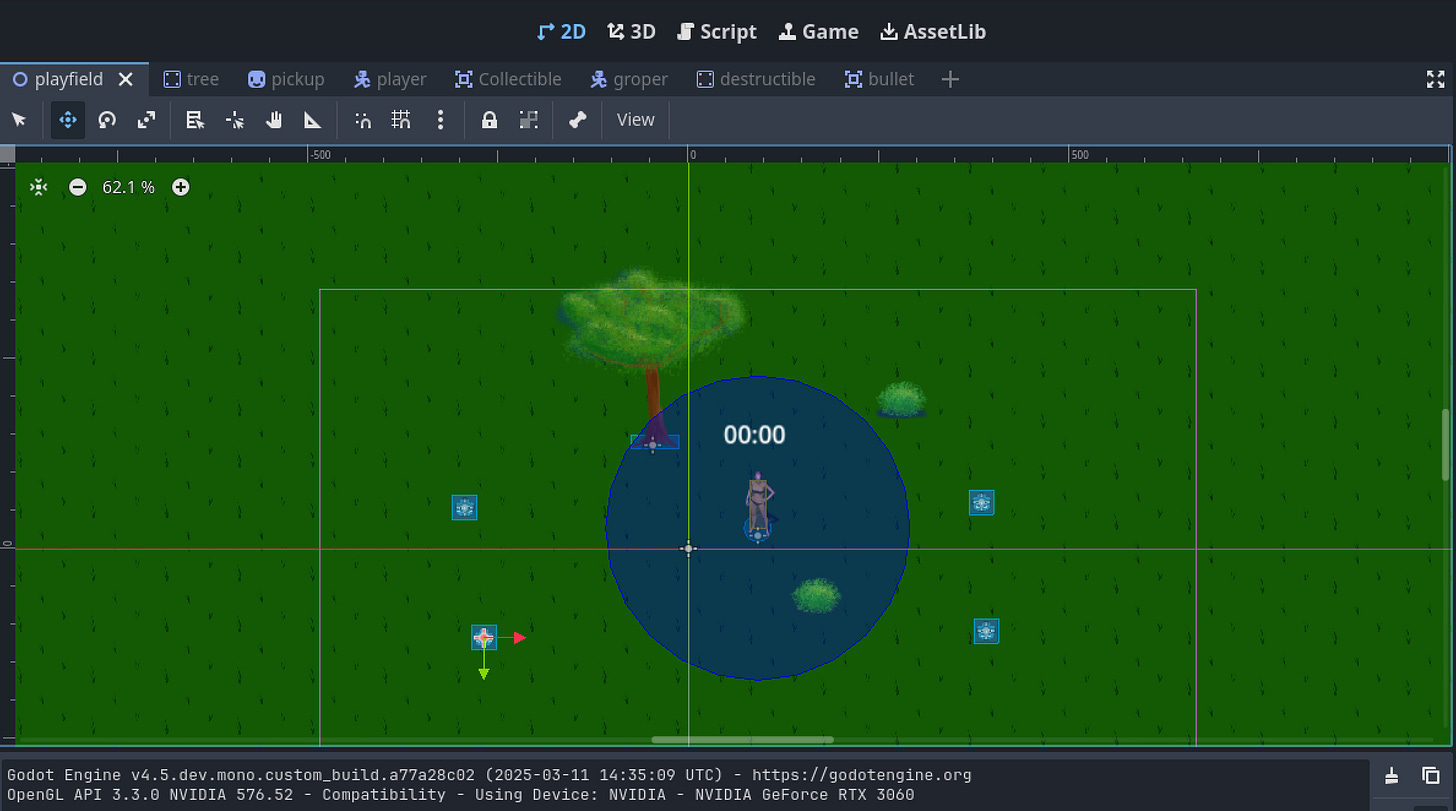

What I’m working up to at the moment is what we call the “vertical slice” - an incomplete game that includes all the elements of the game, in such a way that while it does not look like the finished game, it can still be played like the finished game. What I have right now is more properly termed a “prototype” - it works, but doesn’t have all the features or all the graphics. But I’m starting to edge into the beginning of vertical slice territory.

Since this is a horde survival roguelite, that means it needs to have a level you can play from beginning to end, and an upgrade shop where you can alter parameters for the next playthrough. The usual loop is to play the level unsuccessfully, losing just a couple minutes in, then use treasure collected during gameplay to buy upgrades that get you a little farther.

Currently, I’m working on that level you play from beginning to end. This is where the player will spend most of their time, after all, and in particular the first few minutes of the first level will be the only part of the game they can play for quite some time.

There’s a vocabulary you develop here that introduces the elements of the game one by one, without being intrusive or confusing. The player should be able to figure out how to move and attack almost immediately, then rapidly learn which elements of the environment are destructible and what the results will be.

All this should happen before any enemy poses a meaningful threat, and the player should be able to rapidly deal with that enemy. Collectible items should drop and the player should be able to figure out how to get them. More enemies should arrive, and the player should get their first example of how advancement works after dispatching them.

All of this should happen in the first ten seconds, and in the next ten to twenty seconds… a new and inexperienced player should face the first real challenge, be overwhelmed, and die.

In my game, this is where you first learn that the enemies can pick up experience, too. A series of enemies will spawn surrounding the player, close enough to one another that when they drop experience the enemy next to them picks it up, and if you don’t deliberately make gaps in the wall - or get close enough to grab the experience yourself - you’re just going to make the enemies stronger.

If you know this is going to happen, or can figure it out fast enough, it’s fairly trivial to avoid. But if you’re surprised by it… chances are good you’re gonna lose here. This is also the place where you probably learn (if you are paying attention) that you lose levels as you take damage.

That checks the last box of what your game has to do on the first run, demonstrating why it is different. Why should the player play again? Why should they keep playing? If you don’t deliver an answer to this the first time they play, you might lose them.

It’s not the same when you tell people in your marketing that your game is different, even if you explain how and why it is different; the player needs to know what it feels like, so they know this difference actually makes the game fun. If it doesn’t, who cares?

For this particular type of game, the first thirty seconds is crucial. If you don’t have a good first thirty seconds, you basically don’t have a game.

There’s other stuff you need in a vertical slice. You need the main menu, you need the major UI elements, if there is a save system you need to implement that, it needs to have all the elements of opening and playing the completed game. Publisher logos, attract loop, menu, options, etc.

The vertical slice could, if you are so inclined, be regarded as a finished demo. I have every intention of using mine in that fashion, it’s going up on itch.io to generate initial interest, and then it will be joined by a scaled-back version of the game with three or four levels. Once I’m fairly satisfied with that, the full version will go up on Steam.

I don’t know how long that’s going to be. This game has been on my to-do list for about four years, and I’ve been actively working on it for six months. I’m a solo dev doing everything on my own, from design to programming to art to music, so it takes a long time.

Not that there is any music yet. Or much art. I’m constantly aware of how much added work there is to be done, like a single enemy currently needs about 80 sprites to handle all the animations and if there are going to be ten different enemies in each of ten different levels that’s eight thousand sprites. It’s an insane amount of work and I really need to figure out how the hell I am ever going to get it all done. If I want to do those sprites in a year, working full time, I need to finish a sprite every 15 minutes.

I don’t think that’s out of the question, really, but this isn’t all of the art and I don’t really want to spend an entire year doing nothing but making sprites anyway. That’s not even half the work. So part of this one level’s design process is establishing whether I can do all the art in less than a month.

Once all the code is in place and it’s all just like, crappy placeholder graphics… I’ll mark the calendar and go “how fast can I make this happen?” which is going to mean roughly a thousand completed sprites. 250 a week, if I want it to happen in a month, so about 50 a day which - in an eight hour day - gives me a little over eight minutes each.

I’ll need to duplicate that for each level, so I could - doing nothing but graphics full time - get the limited release out in another two or three months, and the full game in just under a year. But since I’ll also have testers and demo users to support, it will probably take somewhat longer.

The good news is that development tends to accelerate for me after I do the early parts. The whole purpose of taking years to think about the design and months to think about the code is so I can zero in on what the core elements are and build the tools to make them. It’s even more than that - it’s designing elements that can be reused in other games, later.

I’ve never built a game like this before. I’ve built management games and board games and arcade games and clicker games, but never anything action-based. A huge amount of this is learning how to do this stuff at all, on the granular level of a code component, and also learning how to do it in Godot.

And do you know what the most annoying part is? Having spent all this time on marketing and sales and writing and coaching and art only to sit back down and start writing code and realise that this is so much easier. I spent my whole life approaching everything by writing code and when I left Microsoft in 2008, I decided to take five years off and write no code at all until 2014. Just to see how other people relate to the world, so I could understand that.

And I did that, and I’ve got a handle on that, and I basically stayed there because it had become my habit. But now that I open up Godot and Visual Studio Code and start writing code, I am just… this is where I belong. What would I do if I couldn’t code? Not much, apparently. This is what I’m good at. This is what I should have kept doing.